During the early days of 5G, the mobile industry was sometimes caught saying that mobile – with the help of 5G – would kill Wi-Fi. That hasn’t happened, obviously. Usage of public Wi-Fi hotspots would likely decline if more users had mobile data plans that are unlimited in volume. T-Mobile suggested it in this blog post from December 2021.

But even if so, few users would stop using their Wi-Fi at home. Home is where Wi-Fi connects automatically and where a majority of usage takes place.

Ironically, the greatest use case for 5G so far is to substitute fixed broadband. 5G has encouraged many MNOs globally to, for the first time, seriously push fixed wireless access, or FWA, services using their mobile networks. Why is it ironic? The mobile industry has for more than a decade specified and built 5G, the most advanced and best mobile technology so far, but its primary use case to date is fixed. Sitting still.

While FWA could substitute a fixed broadband connection, especially DSL and cable, it does not substitute Wi-Fi, though. The FWA router converts 5G into Wi-Fi. Wi-Fi, not 5G, remains the interface to the connected devices in the home.

So while we, already, are tired of our own headline and the whole notion of “Wi-Fi vs. 5G”, we need to check the facts. After all, we are Tefficient and believers in data.

For more than ten years, we have made our analyses of mobile data usage, drivers and revenue public to you all. If you haven’t read it, find one of the latest here: Data-only drives traffic. The same can’t be said for 5G.

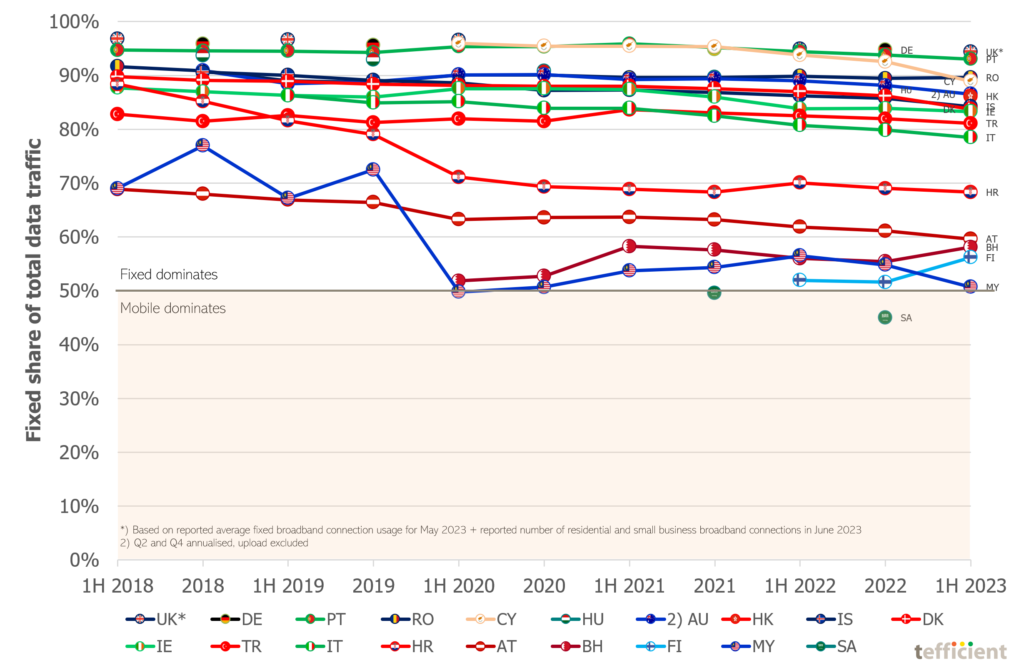

In order to make these analyses we track the official telecom statistics of about 50 countries worldwide. Nineteen of these countries report the fixed data traffic in addition to the mobile data traffic. For these, we can see if 5G led to a changing balance between the fixed data traffic and the mobile data traffic.

Let’s first establish that 18 of 19 countries, Germany to Malaysia, are in the top half of our chart where the fixed data traffic is larger than the mobile data traffic. In just one country, Saudi Arabia, is the mobile data traffic larger than the fixed data traffic.

Germany is the country with the highest share of traffic on fixed, 95%. Saudi Arabia has the lowest share of traffic on fixed, 45%.

Secondly, let’s establish that in 13 of 19 countries, Germany to Italy, the fixed data traffic totally dominates the mobile data traffic – each with more than 78% of the traffic being carried by fixed networks. That’s also close to the average of our nineteen markets: 77%.

But six countries, Croatia, Austria, Bahrain, Finland, Malaysia and Saudi Arabia, have a different characteristic. Here fixed just represents in between 45% and 68% of the total data traffic of a country. From our mobile data usage analysis we know that these countries have very high average mobile data usage – they are all in the top 7 of the world (of 49). Wide availability of offers with unlimited mobile data is a key characteristics of these six markets.

Our analysis also shows that these countries tend to have a large share of their mobile subscriptions in the data-only and FWA segments. No wonder that their mobile data traffic is high when it substitutes or mimics fixed access services.

But if we start to look for the time trends in our graph above, aren’t the lines generally dipping a bit, i.e. fixed is losing some of its dominance? Let’s visualise the year-on-year trends.

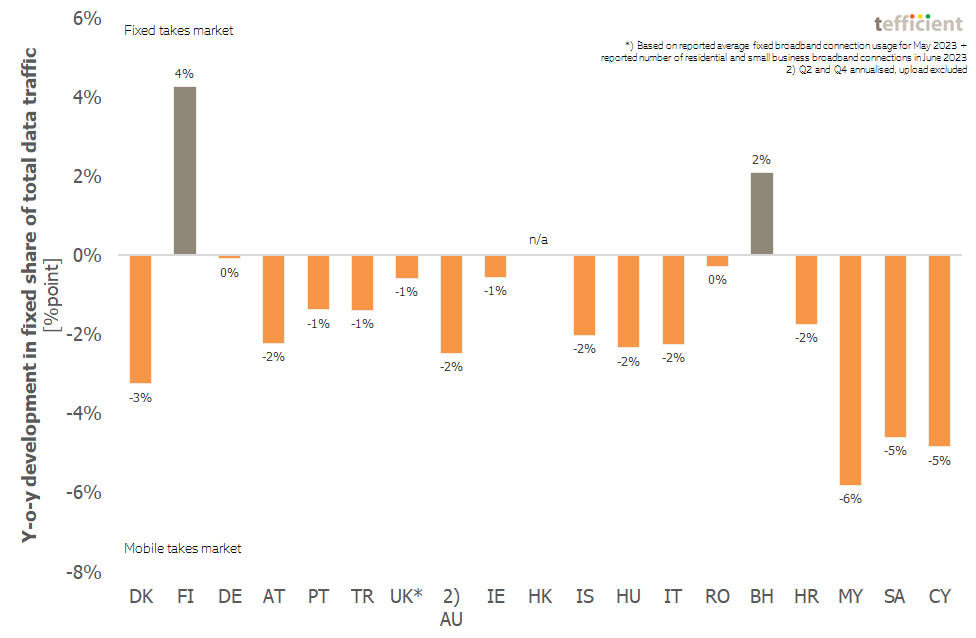

We have the necessary historical data for 18 of the 19 countries. Of these 18, just two, Finland and Bahrain, experienced a positive development in the fixed share of the total data traffic. In Finland it grew by 4 percentage points, in Bahrain by 2 percentage points. The fixed data reporting of Finland was however introduced as late as the first half of 2022 and it could be that it was under-reported during 2022.

In the remaining countries – 16 of 18 – the fixed share of the total data traffic shrunk in the past year. Fixed is actually losing some ground to mobile.

We do think this is an effect of 5G, but only indirectly. For many MNOs, 5G was the catalyst for launching FWA propositions. And since the average FWA user might well consume 334 GB per month [a number for Australia in 1H 2023, see Figure 10 in our analysis], 20x the average mobile usage, even a small number of FWA users will make a difference.

Fixed loses some of its dominance to mobile – but Wi-Fi doesn’t.

In the home it doesn’t matter if the router is fed by fibre, cable, DSL or 5G; the devices are on Wi-Fi. So although our figures show that fixed loses some of its traffic dominance to mobile, Wi-Fi doesn’t.