Even though there are some high-profiled exceptions (Verizon, most of Vodafone Group and Free to mention three), few telcos are today trusting its ability to attract all customer segments – across consumer and business markets – with one single brand.

Having one or several sub-brands has become the norm of a modern telco. In some cases, e.g. with KPN’s Telfort and TDC’s Telmore, sub-brands have been added as a result of acquisitions (often of a successful disruptive brand). In other cases, e.g. Orange’s Sosh or 3 Denmark’s Oister, telecos have themselves created the sub-brand – often with the intention to isolate the main brand from a new price fighter brand.

Hiding the motherhood or promoting it?

![]() Some telcos try to make their sub-brand appear as it has nothing to do with them. AT&T’s acquired Cricket sub-brand is one such example.

Some telcos try to make their sub-brand appear as it has nothing to do with them. AT&T’s acquired Cricket sub-brand is one such example.

Other telcos have started to attach some of the qualities of its main brand to its sub-brand. Orange’s Sosh (created) is such an example. The Sosh logo is today clearly showing the motherhood of Orange.

Other telcos have started to attach some of the qualities of its main brand to its sub-brand. Orange’s Sosh (created) is such an example. The Sosh logo is today clearly showing the motherhood of Orange.

![]() And then there are the telcos where the sub-brand has been integrated. Bouygues’ B&YOU (created) is one example. Today the B&YOU plans have come to represent non-binding plans in general and are offered side-by-side with Bouygues’ other plans on its main website.

And then there are the telcos where the sub-brand has been integrated. Bouygues’ B&YOU (created) is one example. Today the B&YOU plans have come to represent non-binding plans in general and are offered side-by-side with Bouygues’ other plans on its main website.

Elisa’s acquired Saunalahti sub-brand was first made the primary mobile brand for consumers, but now it seems as if Elisa gradually wants it to be forgotten (but not quite) since the consumer logo today looks like this.

Elisa’s acquired Saunalahti sub-brand was first made the primary mobile brand for consumers, but now it seems as if Elisa gradually wants it to be forgotten (but not quite) since the consumer logo today looks like this.

![]() In certain cases, the sub-brand can even replace the original brand. The Danish incumbent, TDC, has announced that it will rebrand its consumer business as YouSee. The YouSee brand was originally created by TDC as a cable TV brand.

In certain cases, the sub-brand can even replace the original brand. The Danish incumbent, TDC, has announced that it will rebrand its consumer business as YouSee. The YouSee brand was originally created by TDC as a cable TV brand.

How successful are the sub-brands?

Good question. With very few exceptions, telcos don’t split up their reporting between the mother brand and the sub-brand(s). And in some cases, we believe telcos don’t want us to know. Many sub-brands have a marginal market share. Or, in some cases, the sub-brand has become too successful and is actually diluting the overall position of the telco when customers of the main brand migrate to the sub-brand. We’ll come back to this, but let’s first look at someone that actually separates out the performance of its sub-brand – Orange France.

Orange’s Sosh grows at the expense of Orange

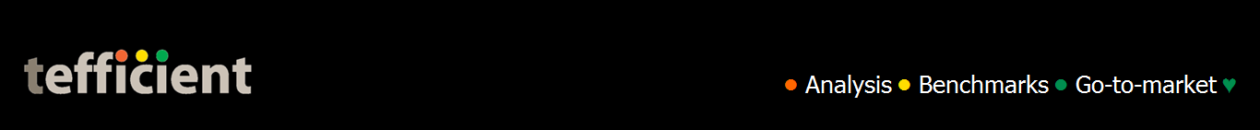

Sosh had close to 3 million customers in December 2015 and its growth rate during these three years was an impressive 170%.

In the same time frame, Orange lost 3% of its total non-M2M mobile customer base. That base includes business customers not addressed by Sosh, but the graph can suggest that Sosh has recruited its customers from the Orange brand.

The Sosh sub-brand was created in anticipation of Free’s mobile launch to mitigate Free’s disruptive impact. Sosh should be cheaper, more straight-forward and simpler than Orange. And sold online. If we in the graph look at Free’s development of its total mobile base (+92%), it’s clear that Orange’s tactic to let the Sosh sub-brand fight Free might been a good one for Sosh, but perhaps not for the full Orange who still lost base. Consequently, Orange has added triple-play to Sosh’s portfolio.

Orange’s blended ARPU fell 16% in the time frame of the graph. The decline has slowed down, though: In the last year, ARPU was just down 1%. The take-up of Sosh has contributed to this ARPU decline, but the situation might well have been worse without Sosh.

MetroPCS behind much of T-Mobile’s growth – and Cricket behind all of AT&T’s

We have often reported about T-Mobile‘s success. Through a series of un-carrier moves, T-Mobile has gone from a total base of 34 million SIMs in Q1 2013 (before the first un-carrier move) to 63 million SIMs in Q4 2015 less than three years later. That’s an added 29 million SIMs. Wow.

We have often reported about T-Mobile‘s success. Through a series of un-carrier moves, T-Mobile has gone from a total base of 34 million SIMs in Q1 2013 (before the first un-carrier move) to 63 million SIMs in Q4 2015 less than three years later. That’s an added 29 million SIMs. Wow.

![]() But all of it isn’t organic. T-Mobile acquired MetroPCS by the end of April 2013 – just after T-Mobile’s first un-carrier move. At that point in time, MetroPCS had about 9 million customers. T-Mobile has now decommissioned the MetroPCS network and expanded the sub-brand to a national one. How many of T-Mobile’s reported customers are actually with MetroPCS? T-Mobile doesn’t say, but we think it’s a big chunk. T-Mobile reports MetroPCS’ customers within its “branded prepaid” segment with close to 18 million customers. In Q4 2015, T-Mobile reported its second best quarterly performance in branded prepaid net customer additions since the combination with MetroPCS in Q2 2013. The success is attributed to MetroPCS by T-Mobile’s management.

But all of it isn’t organic. T-Mobile acquired MetroPCS by the end of April 2013 – just after T-Mobile’s first un-carrier move. At that point in time, MetroPCS had about 9 million customers. T-Mobile has now decommissioned the MetroPCS network and expanded the sub-brand to a national one. How many of T-Mobile’s reported customers are actually with MetroPCS? T-Mobile doesn’t say, but we think it’s a big chunk. T-Mobile reports MetroPCS’ customers within its “branded prepaid” segment with close to 18 million customers. In Q4 2015, T-Mobile reported its second best quarterly performance in branded prepaid net customer additions since the combination with MetroPCS in Q2 2013. The success is attributed to MetroPCS by T-Mobile’s management.

![]() How can MetroPCS be so successful – without all the un-carrier initiatives of T-Mobile? As a matter of fact, certain un-carrier moves have spread to MetroPCS. Music Unlimited (which zero-rates most music streaming services) is one. T-Mobile calls this Music Freedom, but it’s essentially the same thing. But MetroPCS customers don’t e.g. get zero-rated video as some T-Mobile customers get with Binge On.

How can MetroPCS be so successful – without all the un-carrier initiatives of T-Mobile? As a matter of fact, certain un-carrier moves have spread to MetroPCS. Music Unlimited (which zero-rates most music streaming services) is one. T-Mobile calls this Music Freedom, but it’s essentially the same thing. But MetroPCS customers don’t e.g. get zero-rated video as some T-Mobile customers get with Binge On.

But as with most sub-brands there is a price differential: MetroPCS is cheaper than T-Mobile – at least for individuals who aren’t into family discounts. MetroPCS’ propositions are also more straight-forward and simple.

But it’s not just an online brand. MetroPCS has a large number of dedicated stores, separate from T-Mobile’s.

But it’s not just an online brand. MetroPCS has a large number of dedicated stores, separate from T-Mobile’s.

T-Mobile’s blended service ARPU fell 3% in 2015.

![]() In its consumer mobilty segment, T-Mobile’s competitor AT&T is only growing in one segment: prepaid. Led by its acquired Cricket sub-brand, AT&T had 11.5 million prepaid customers in December 2015. In the past year, AT&T added 1.5 million prepaid customers net while losing 1.8 million postpaid consumer customers. Cricket’s propositions are cheaper, more straight-forward and simpler than

In its consumer mobilty segment, T-Mobile’s competitor AT&T is only growing in one segment: prepaid. Led by its acquired Cricket sub-brand, AT&T had 11.5 million prepaid customers in December 2015. In the past year, AT&T added 1.5 million prepaid customers net while losing 1.8 million postpaid consumer customers. Cricket’s propositions are cheaper, more straight-forward and simpler than  AT&T. Also Cricket has it owns stores.

AT&T. Also Cricket has it owns stores.

AT&T’s service ARPU in the Consumer Mobility segment fell 4% in 2015 which partly could be attributed to the sub-brand success.

Oister & Hallon behind much of 3’s growth in Denmark & Sweden

Already in 2008 ‘3’ created the Oister sub-brand in Denmark. Originally it was just a mobile broadband proposition, but was later expanded into a full sub-brand of ‘3’. The company has about 1.2 million customers in Denmark – but we believe a large share are actually with Oister. And, yes, even though 3’s propositions aren’t expensive or complicated, Oister’s are still cheaper and simpler. Oister is an online brand with some dealer presence but doesn’t have any stores.

Already in 2008 ‘3’ created the Oister sub-brand in Denmark. Originally it was just a mobile broadband proposition, but was later expanded into a full sub-brand of ‘3’. The company has about 1.2 million customers in Denmark – but we believe a large share are actually with Oister. And, yes, even though 3’s propositions aren’t expensive or complicated, Oister’s are still cheaper and simpler. Oister is an online brand with some dealer presence but doesn’t have any stores.

3’s blended service ARPU fell 6% in 2015 in spite of continuous high mobile data usage and growth.

3’s blended service ARPU fell 6% in 2015 in spite of continuous high mobile data usage and growth.

![]() It took until 2013 for ‘3’ to take a similar setup as Oister across the bridge to Sweden. The Swedish sub-brand is called Hallon. We believe a large share of the reported base growth in ‘3’ is actually because of Hallon which features a cheaper, less complicated, proposition compared to ‘3’. Hallon is

It took until 2013 for ‘3’ to take a similar setup as Oister across the bridge to Sweden. The Swedish sub-brand is called Hallon. We believe a large share of the reported base growth in ‘3’ is actually because of Hallon which features a cheaper, less complicated, proposition compared to ‘3’. Hallon is  an online brand.

an online brand.

The effect on ARPU isn’t visible (yet?): 3’s blended service ARPU was flat in 2015 in spite of continuous high mobile data usage and growth.

KPN turned Telfort into a mini-KPN

![]() The Telfort brand came to KPN through an MNO acquisition back in 2005. In constrast to another KPN consumer sub-brand which KPN killed in 2015, Hi, KPN has developed Telfort – into a multi-service brand.

The Telfort brand came to KPN through an MNO acquisition back in 2005. In constrast to another KPN consumer sub-brand which KPN killed in 2015, Hi, KPN has developed Telfort – into a multi-service brand.

Telfort is today more or less a mini-KPN with all the bells and whistles of the mother brand – multi-play bundles, combination discounts and business offers.

It even has it own stores, occasionally side by side with KPN’s as in this case.

It even has it own stores, occasionally side by side with KPN’s as in this case.

Since Telfort offers the same as KPN, just a bit cheaper and simpler, it’s not unrealistic that it’s the Telfort sub-brand that is behind much of the base growth KPN has shown in 2015. The consumer retail ARPU of KPN has been stable in 2015 though – but then the mobile data usage doubled during the year.

More on KPN and its quad-play strategy

TDC’s complex sub-brand past – and YouSee future

We already mentioned that TDC is about to rebrand as YouSee in the consumer space in Denmark. To draw a parallel it’s as if BT would rebrand to Plusnet. Over the years, TDC acquired in essence all of the successful independent brands in Denmark – Telmore, Fullrate, M1, Onfone – to turn them into TDC sub-brands. For some time the best way to become a millionaire in Denmark was to set up an online MVNO, dump the prices, get a few hundred thousand customers and wait to be acquired by TDC (or occassionally TDC’s competitors).

To begin with, TDC expanded on the scope of the acquired sub-brands, making their portfolio wider, but during the last years, TDC discontinued some of the sub-brands (M1, Onfone). On the other hand the company expanded the YouSee brand to include also mobile – for both individuals and businesses.

To begin with, TDC expanded on the scope of the acquired sub-brands, making their portfolio wider, but during the last years, TDC discontinued some of the sub-brands (M1, Onfone). On the other hand the company expanded the YouSee brand to include also mobile – for both individuals and businesses.

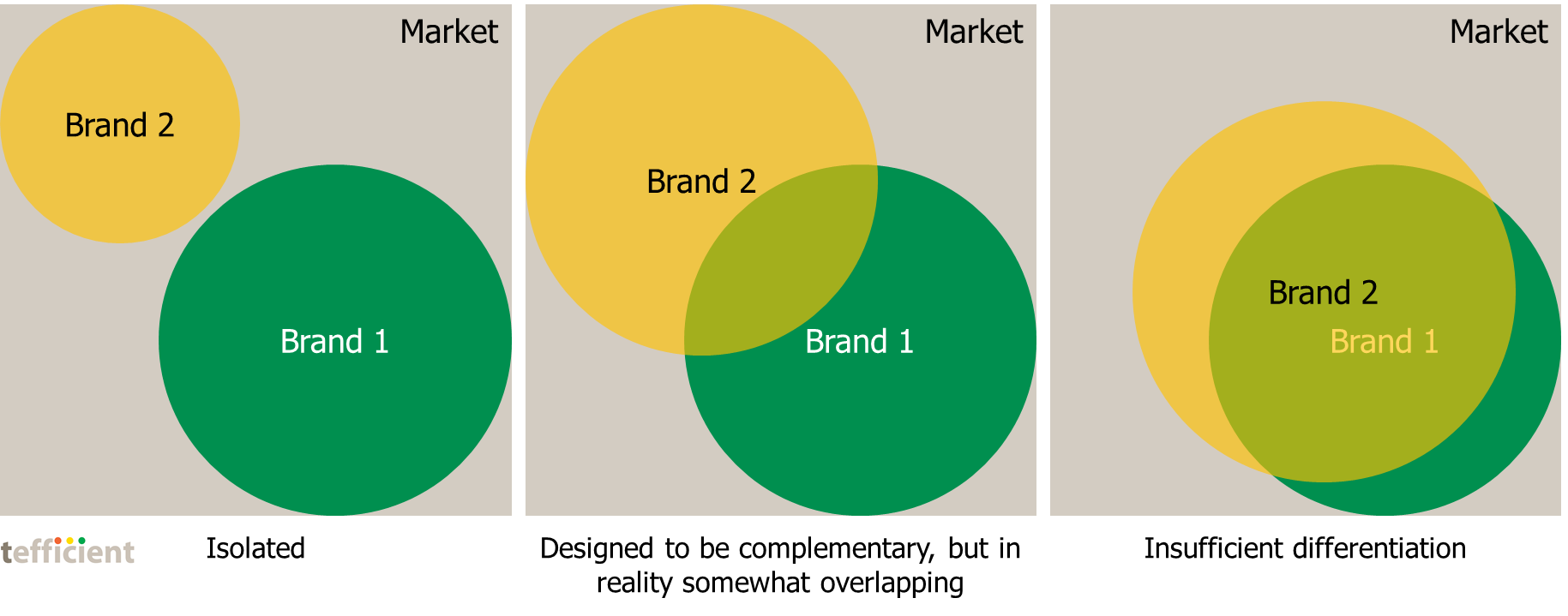

It’s clear that a large share of TDC’s mobile base in the market – both consumer and business – isn’t with the TDC brand but the sub-brands. Telmore indicates around 600 thousand customers which is 30% of TDC’s consumer base. The mobile ARPU development (excl. data-only) of TDC as a whole isn’t pretty (see graph). But whereas TDC lost a lot of market share in the consumer segment (where ARPU has been standing up better), TDC has been able to defend market share in the business segment (where ARPU really has come down). At the same time, TDC’s mobile data usage has skyrocketed in the first half of 2015 – up 192%.

It’s clear that a large share of TDC’s mobile base in the market – both consumer and business – isn’t with the TDC brand but the sub-brands. Telmore indicates around 600 thousand customers which is 30% of TDC’s consumer base. The mobile ARPU development (excl. data-only) of TDC as a whole isn’t pretty (see graph). But whereas TDC lost a lot of market share in the consumer segment (where ARPU has been standing up better), TDC has been able to defend market share in the business segment (where ARPU really has come down). At the same time, TDC’s mobile data usage has skyrocketed in the first half of 2015 – up 192%.

The new management team of TDC has raised the lowest mobile price points twice already and also expressed that they no longer will host market disruptors.

More on TDC and Denmark after the non-merger

Tele2’s Comviq with Sweden’s happiest customers

![]() Like ‘3’, Tele2 has a dual-brand strategy in Sweden. Tele2’s strategy has been around much longer, though. Interestingly, it’s the original mobile brand, Comviq, that today serves as Tele2’s price fighting sub-brand.

Like ‘3’, Tele2 has a dual-brand strategy in Sweden. Tele2’s strategy has been around much longer, though. Interestingly, it’s the original mobile brand, Comviq, that today serves as Tele2’s price fighting sub-brand.

We have written about Tele2’s Tele2.0 transformation but in this context it’s important to have in mind that it doesn’t affect the Comviq sub-brand. And based on the comments given by Tele2’s management in its year-end report, it might well be so that it’s the Comviq brand, not the Tele2 brand, that’s Tele2 primary acquisition vehicle in Sweden now: “Consumer mobile postpaid grew mid-single digit, driven by Comviq“.

We have written about Tele2’s Tele2.0 transformation but in this context it’s important to have in mind that it doesn’t affect the Comviq sub-brand. And based on the comments given by Tele2’s management in its year-end report, it might well be so that it’s the Comviq brand, not the Tele2 brand, that’s Tele2 primary acquisition vehicle in Sweden now: “Consumer mobile postpaid grew mid-single digit, driven by Comviq“.

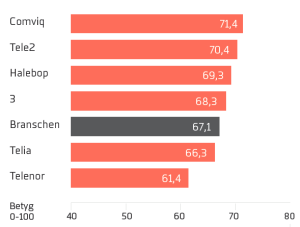

According to Svenskt Kvalitetsindex, Comviq’s customers are also the most satisfied in the Swedish consumer market in 2015, something Tele2 several times highlights.

According to Svenskt Kvalitetsindex, Comviq’s customers are also the most satisfied in the Swedish consumer market in 2015, something Tele2 several times highlights.

Based on reported end-user service revenue, Tele2’s blended ARPU fell 2% in 2015.

What to do when the sub-brand takes over?

We have touched upon eight cases where it appears as if the sub-brand has taken over sales – or at least is close to:

- Orange, France

- T-Mobile, USA

- AT&T, USA

- 3, Denmark

- 3, Sweden

- KPN, the Netherlands

- TDC, Denmark

- Tele2, Sweden

What’s wrong in being successful? Nothing, but the word “cannibalisation” is quite popular within telcos.

What happens when your successful sub-brand starts to become too successful so that it doesn’t only take market share from competition, but starts to migrate your own customers from your premium brand to your sub-brand?

Do you then think of it as cannibalisation:

- Kill the brand – like TDC did with some sub-brands (or KPN did with Hi)?

- Make the brand less attractive – like TDC did when it raised the lowest price points?

or think of it as an opportunity:

- Integrate the brand into your regular brand – like Bouygues’ B&YOU?

- Widen the portfolio of the brand, adding multi-play – like KPN’s Telfort, TDC’s YouSee or Orange’s Sosh?

- Widen the distribution of the brand, adding dedicated stores – ending up with a situation like T-Mobile’s MetroPCS, AT&T’s Cricket or KPN’s Telfort?

- Adopt the brand as your primary brand – like TDC with YouSee?

The “how to” part

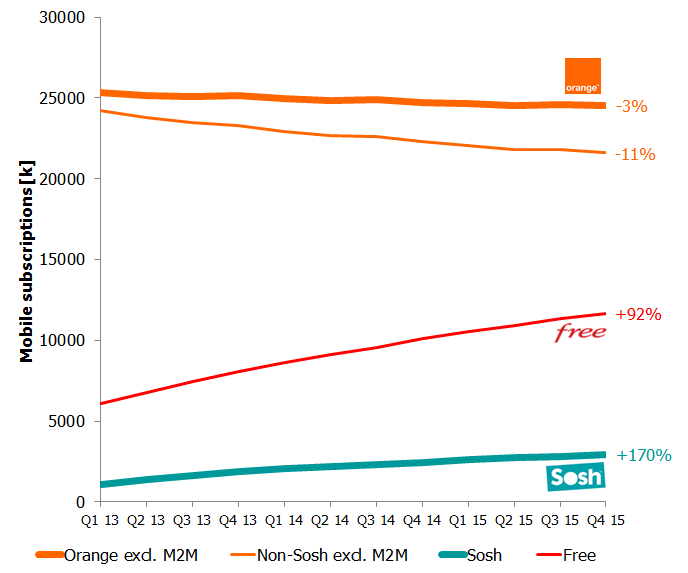

The key to a successful dual-brand strategy is sufficient differentiation between the brands. The last four bullets above are rather making the two brands replaceable and risk to eventually dilute the ARPU of the entire customer base. To widen the portfolio or the distribution is also adding cost, so margin can be hurt two ways.

When the two brands are largely replaceable, we’ve come to a situation as in the right picture below. The reach of both brands is, stand-alone, as high as it can be, but since the overlaps are so significant, the total reach is actually less than in the picture in the middle.

At the same time, the two brands don’t need to be totally isolated from each other (as in the left picture) since too much of the market is then left unaddressed.

If the intention is to design two complementary brands, the reality is that they will still overlap a bit like in the picture in the middle. Since the total reach is maximised this way, it’s OK. Some customers will choose the “wrong” brand (in your view), most often the cheaper, but the negative effect on ARPU and profitability is still limited.

When considering – or reconsidering – your dual-brand strategy, think about how to effectively differentiate the two brands without isolating them too much:

- Online-only sales vs. storefront-also?

- Online-only customer service vs. voice-also?

- No device (SIM-only) vs. device-also?

- No device financing vs. financing?

- Single-play vs. multi-play (discounts)?

- Single-user vs. multi-user (discounts)?

- No link between the brands vs. link?

- Prepaid-only vs. postpaid-also?

- Consumer vs. business?

- No inclusive services vs. inclusive services

- Service bundle size

- Price