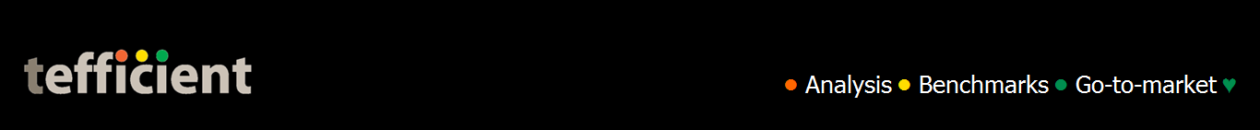

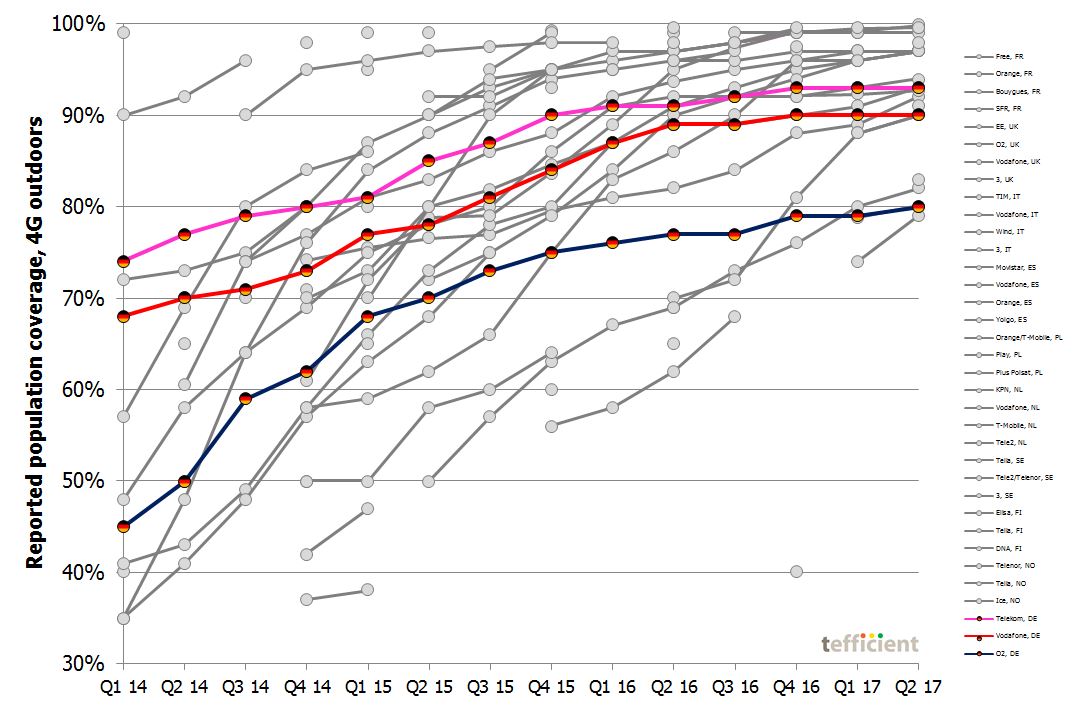

Look at the graph below. It should satisfy mobile end-users, operators, regulators, politicians and equipment suppliers.

It shows that all operators have improved 4G coverage to the extent that they all (well almost) reach above 90% of the population by the end of June.

Mission accomplished then?

Not quite. The graph shows what mobile operators favour to report: Share of population covered by 4G. On the address where people live. Outdoors.

This is hardly representative for the most common use case. People do spend time inside their home. In addition, they spend time outside their home and then not just in their garden – at work, in school, commuting, with friends, shopping, sightseeing – you get it.

Already in 2015 we wrote a blog post called Marketing vs. reality which compared reported 4G coverage with crowdsourced data to find that most operators overstated 4G coverage. We made a more detailed analysis of the Nordics in this piece in 2016.

Indoor coverage

The reason why operators are reporting outdoor population coverage is partly because of the propagation calculation methods used: There’s not enough information on houses and how they are built to be able to calculate indoor coverage with very good accuracy. But the other part of the explanation is likely more important: The numbers look more impressive if they are based on outdoor propagation.

![]() A handful of European operators are still communicating indoor population coverage: Orange in Poland, Proximus and Orange in Belgium, HT in Croatia and Tele2 in the Netherlands.

A handful of European operators are still communicating indoor population coverage: Orange in Poland, Proximus and Orange in Belgium, HT in Croatia and Tele2 in the Netherlands.

Even though not necessarily providing the full truth, it gives mobile end-users a better picture of what coverage they can expect in the most common – indoor – use case.

Geographic coverage

Of the four mentioned countries, Poland and the Netherlands are in our sample for this post: It contains the six most populated countries in Europe: Germany, France, the UK, Italy, Spain and Poland – together with four less populated countries: the Netherlands, Sweden, Finland and Norway.

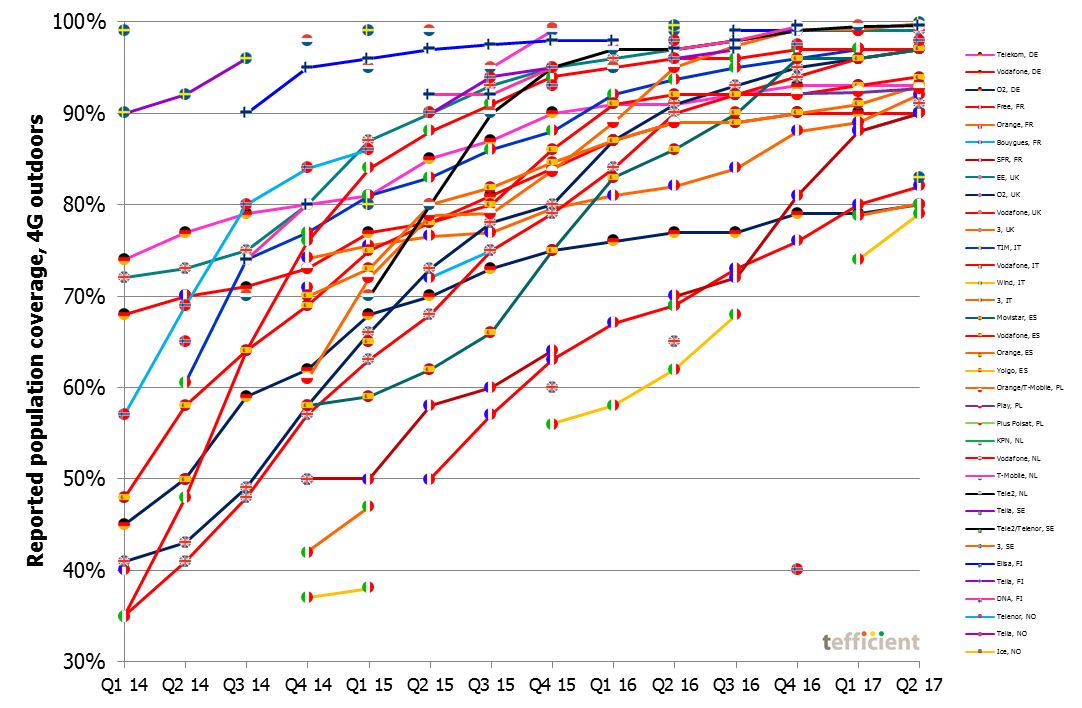

A number of operators in these countries are trying to change the the industry habit of reporting outdoor population coverage to something more representative: Geographic coverage, i.e. how large share of the country landmass is covered. Outdoors.

How much lower is then a geographical coverage figure compared to a population coverage figure? Well, for four of the networks in the graph, we can calculate it:

- EE, UK: 16 percentage points lower

- Tele2/Telenor*, Sweden: 10 percentage points lower

- Orange/T-Mobile*, Poland: 3 percentage points lower

- Tele2, the Netherlands: 3 percentage points lower

*) Shared network

Quite a large difference, isn’t it? In the UK it seems much tougher to cover landmass than population – whereas it in Poland and the Netherlands seems pretty much the same.

An possible explanation is of course how the population is distributed geographically in a country.

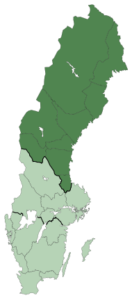

Let’s take Sweden as an example. With 450 thousand square kilometers, it’s the fourth largest country in Europe. The northern, dark green, half of the country, houses 9% of the Swedish population. By just covering the south half of Sweden, an operator could have up to 91% population coverage – with just 50% geographical coverage.

Let’s take Sweden as an example. With 450 thousand square kilometers, it’s the fourth largest country in Europe. The northern, dark green, half of the country, houses 9% of the Swedish population. By just covering the south half of Sweden, an operator could have up to 91% population coverage – with just 50% geographical coverage.

In the Netherlands, a country with much higher population density, the population isn’t evenly distributed either: Close to half of the Dutch population lives in the Randstad area which roughly is 20% of the landmass. But where Sweden – mainly in the north – has large mountain and forest areas where basically nobody lives (permanently; remember the address thing), all of the Netherlands is populated even though not crowded everywhere. So in order to cover the Dutch population well, you automatically get geographical coverage.

Leading and trailing operators

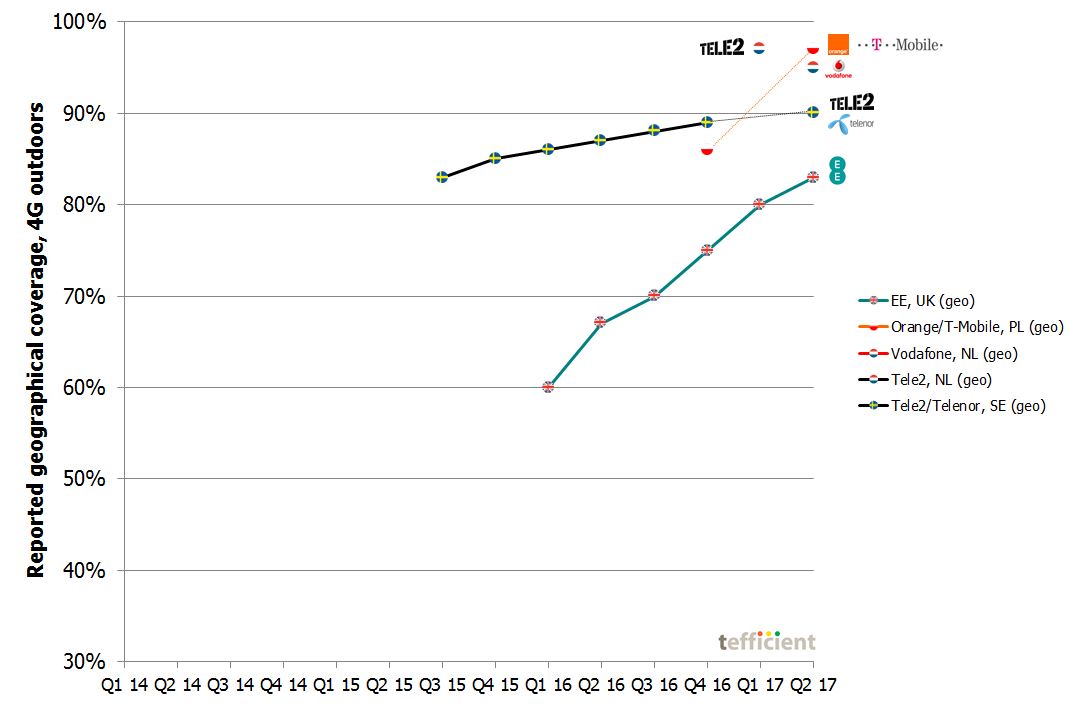

Now that we realise the ifs and buts of reported population coverage, let’s revert to the original graph and identify some of the outliers (click to enlarge).

![]()

![]() Already in the first half of 2013, Tele2 and Telenor in Sweden (highlighted in the upper left corner) communicated that their joint 4G network, Net4Mobility, had reached a population coverage of 99%. Four years later, only six other networks in our sample have reached or crossed that 99% point. In those four years, Tele2/Telenor went from 99% to 99,9% which might sound as if they didn’t do much – but the geographical coverage increased from 70% to 90% in the same time period. Telia has been behind Tele2/Telenor throughout and even if the difference today likely is small, Telia has not seconded Tele2/Telenor’s new habit of reporting geographical 4G coverage.

Already in the first half of 2013, Tele2 and Telenor in Sweden (highlighted in the upper left corner) communicated that their joint 4G network, Net4Mobility, had reached a population coverage of 99%. Four years later, only six other networks in our sample have reached or crossed that 99% point. In those four years, Tele2/Telenor went from 99% to 99,9% which might sound as if they didn’t do much – but the geographical coverage increased from 70% to 90% in the same time period. Telia has been behind Tele2/Telenor throughout and even if the difference today likely is small, Telia has not seconded Tele2/Telenor’s new habit of reporting geographical 4G coverage.

![]() The Dutch incumbent KPN (highlighted to the upper left) started its 4G rollout early. Already in Q1 2014, the company declared that it had reached “nationwide” coverage. Even though the rollout had been substantial, the word was likely invented by the marketeers, not the engineers: Two years later KPN communicated 99,3% population coverage. Very good, but still not “nationwide”. The three competing networks Vodafone, T-Mobile and Tele2 have closed most of the gap to KPN today. T-Mobile, that continues to win network tests, might well have passed KPN, but the Dutch operators seem to have lost most of the appetite to communicate coverage numbers by now.

The Dutch incumbent KPN (highlighted to the upper left) started its 4G rollout early. Already in Q1 2014, the company declared that it had reached “nationwide” coverage. Even though the rollout had been substantial, the word was likely invented by the marketeers, not the engineers: Two years later KPN communicated 99,3% population coverage. Very good, but still not “nationwide”. The three competing networks Vodafone, T-Mobile and Tele2 have closed most of the gap to KPN today. T-Mobile, that continues to win network tests, might well have passed KPN, but the Dutch operators seem to have lost most of the appetite to communicate coverage numbers by now.

![]() The Finnish operator Elisa (upper left) at first reported sky high population coverage figures for 4G since it included Dual Carrier 3G. In Q3 2014, Elisa stopped this habit and have since expanded its 4G network to at least 99% population coverage. Competition was initially behind, but since the formation of the rural network sharing JV between Telia and DNA, DNA has communicated higher and higher figures. DNA reported 99,6% population coverage in June. Elisa, on its hand, has not provided any update since Q4 2016 when it was at 99%.

The Finnish operator Elisa (upper left) at first reported sky high population coverage figures for 4G since it included Dual Carrier 3G. In Q3 2014, Elisa stopped this habit and have since expanded its 4G network to at least 99% population coverage. Competition was initially behind, but since the formation of the rural network sharing JV between Telia and DNA, DNA has communicated higher and higher figures. DNA reported 99,6% population coverage in June. Elisa, on its hand, has not provided any update since Q4 2016 when it was at 99%.

If these were the leading operators, the trailing operators are found in the lower right-hand side of the graph.

![]() The two Italian operators Wind and 3 have just merged their operations into a 50/50 held JV. It’s difficult to say what is the chicken and what is the egg of this merger, but the graph is showing that the individual 4G networks of Wind and 3 are not just lagging behind rest of Europe, but most importantly behind local competitors Vodafone and TIM. A challenge for Wind 3 going forward is that the two networks likely are overlapping to a large extent which means that the significant coverage delta to Vodafone and TIM will remain even after an integration of the two networks.

The two Italian operators Wind and 3 have just merged their operations into a 50/50 held JV. It’s difficult to say what is the chicken and what is the egg of this merger, but the graph is showing that the individual 4G networks of Wind and 3 are not just lagging behind rest of Europe, but most importantly behind local competitors Vodafone and TIM. A challenge for Wind 3 going forward is that the two networks likely are overlapping to a large extent which means that the significant coverage delta to Vodafone and TIM will remain even after an integration of the two networks.

![]() It shouldn’t surprise anyone that the French challenger Free comes out of a position as a 4G coverage laggard. Launched as late as in 2012 and with a regulatory coverage requirement on 3G to fulfill first, Free has taken a step at a time. Free has also had a fallback in a national roaming agreement with Orange and used Wi-Fi cleverly for offload. Since mid 2015, the 4G rollout has been steady and fast, though. In our sample, Free has not only passed Wind and 3 Italy but also O2 Germany even though that network is the result of two integrated networks: O2 and E-plus.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that the French challenger Free comes out of a position as a 4G coverage laggard. Launched as late as in 2012 and with a regulatory coverage requirement on 3G to fulfill first, Free has taken a step at a time. Free has also had a fallback in a national roaming agreement with Orange and used Wi-Fi cleverly for offload. Since mid 2015, the 4G rollout has been steady and fast, though. In our sample, Free has not only passed Wind and 3 Italy but also O2 Germany even though that network is the result of two integrated networks: O2 and E-plus.

Since Altice acquired and took over SFR, the company has been bleeding customers. Similar to Free, the 4G coverage has been much behind that of Orange and Bouygues Telecom. But the trend since Q3 2016 is very encouraging; SFR has rapidly expanded its 4G coverage and is now a similar level as Orange and Bouygues.

![]() Finally, Ice of Norway which just recently communicated that in the end of 2016, it covered 40% of the Norwegian population with 4G. You have to go back two years to find similarly low figures in our graph (and longer than that for Norway). Ice can manage the customer experience through its national roaming agreement with Telia, but the company management has now set a target for 80% population coverage to be reached in the first half of 2018. In a country obsessed with coverage and where the Telia vs. Telenor coverage battle is reported weekly, Ice’s ability to impress is limited.

Finally, Ice of Norway which just recently communicated that in the end of 2016, it covered 40% of the Norwegian population with 4G. You have to go back two years to find similarly low figures in our graph (and longer than that for Norway). Ice can manage the customer experience through its national roaming agreement with Telia, but the company management has now set a target for 80% population coverage to be reached in the first half of 2018. In a country obsessed with coverage and where the Telia vs. Telenor coverage battle is reported weekly, Ice’s ability to impress is limited.

The German enigma

Over and over again, our mobile data usage analysis has shown how uniquely positioned Germany is in Europe with its very low average mobile data usage and its very high effective revenue per gigabyte. It also features low smartphone, low 4G and low data-only penetration.

Over and over again, our mobile data usage analysis has shown how uniquely positioned Germany is in Europe with its very low average mobile data usage and its very high effective revenue per gigabyte. It also features low smartphone, low 4G and low data-only penetration.

Also in fixed broadband, we have had our doubts about Germany’s readiness for the future.

If we revert to the 4G population coverage graph to identify the three German networks, it’s clear that the country isn’t expanding 4G coverage at all as fast as the other operators in Europe.

The absolute positions of Telekom and Vodafone were alright by the end of 2015, but since then the German 4G networks haven’t gained much coverage at all – at the same time as operators like Orange/T-Mobile Poland, O2/Vodafone UK, Movistar and SFR have shown their capability to spurt. O2 Germany is expanding its network faster than Telekom and Vodafone Germany but is anyhow nowhere near to threaten the two incumbents.

Unless Germany gets its act together soon, the remaining Italian and French laggards will soon also pass Telekom and Vodafone Germany.

One of our Twitter followers, Joaquin Guerrero couldn’t understand why Europe’s largest economy is in this situation and called it the German enigma. We are puzzled by it too.

To sum up

Germany aside: The European 4G networks are quickly expanding their respective coverage areas. Competition drives operators to invest more and to constantly improve their networks. Bur our blog shows that the mission isn’t accomplished just because a network reaches 99% – or even 100% – of the population outdoors.

Operators: If you want to show that you are leading, start communicating indoor coverage and start communicating geographical coverage. Why not both?